(10) The Zero AI Edition

A quick intro to BCIs and their three main psychological applications. Deep Dive into the online group therapy provider Peers. This week's most important news and research in psych tech.

Currently, there is almost no mental health tech innovation that doesn't involve Generative AI. Or so does it seem!

There are plenty other stories, companies and people out there, worth looking at. That is why this week, you will find no Gen AI in the following lines.

Psych Startup Highlight of the Week:

- Peers. Access to psychological support, somewhere between group therapy and self-help groups. A deep dive into business model, products and company history.

This week's top story:

- A quick intro into BCIs. Brain computer interfaces come in many different forms. I will give a broad overview and then focus in on mental health applications.

Odd Lots – News & Research:

- Digital prescriptions for DiGAs delayed to early 2026 (News, GER)

- Interview with CEO of the UK Advanced Research & Invention Agency (Article)

- AR Systems to give a voice to non-verbal autism (Article)

- Former CEO of 23andMe outbids pharmaceuticals giant who was set to buy the company (News)

I. A Primer on BCIs for Mental Health.

Whilst the technology is still very early, some products already claim to deliver tangible benefits.

Brain Computer Interfaces have been around for decades. But they are far from the sci-fi mind-reading that any good dystopian novel contains. They come in different shapes, utilize varying technologies and resulting products are very different in their core functionality. My goal here is to provide a short fundamental overview of the tech and then get into applications within the realm of psychology. This is not an absolute summary, nor am I an expert. I am just as curious as you are. Additional resources will be linked at the end.

A Short History Lesson

The term “brain–computer interface” was coined by researcher Jacques J. Vidal in 1973. Vidal imagined that one day electrical signals from the brain could directly control computers and prosthetic devices. He saw BCIs as a way to restore communication and movement to patients with paralysis by decoding their neural activity. Of course, in 1973 both EEG technology and computers were primitive: data acquisition hardware was slow and low‐resolution, and available processors couldn't handle the necessary processing.

Over the next decades BCI research was slow. Until in 2004, the first paralyzed human, Matt Nagle, used an implant called BrainGate to move a cursor on a screen. This early success required invasive electrodes and heavy computing. Even so, it validated Vidal’s concept and showed that BCIs could translate intent into action, thoughts into machine instructions.

Since then, exponential improvements in microelectronics, sensors, and algorithms have driven the field toward Vidal’s goal of hands-free control of computers and robots by thought alone. But the tech is still in experimental trial phases.

How to Approach BCI Tech

Today’s BCIs come in many flavors, distinguished by how they record brain activity, how (if at all) they stimulate the brain, and how invasive the technology is. Here are some key parameters that will help you navigate the space an ask the right questions at the next conference to sound smart:

- Signal acquisition: EEG (electroencephalography) uses scalp electrodes to measure voltage from large neuron populations, and is by far the most common non-invasive approach (as it is low cost and safe). MEG (magnetoencephalography) uses helmet-like sensors to record magnetic fields, but is bulky and lab-bound. fMRI (functional MRI) and fNIRS (functional near-infrared spectroscopy) use blood-oxygen signals (fMRI via MRI scanners, fNIRS via wearable optical sensors) to infer brain activity. These hemodynamic methods have better spatial resolution but poorer time resolution than EEG. They are also least common as miniaturization is a major limiting factor.

- Brain stimulation methods: Some BCIs are bidirectional, not only reading signals but also stimulating the brain. Non-invasive stimulation includes TMS (transcranial magnetic stimulation), which pulses magnetic fields to induce currents in the brain, and tDCS (transcranial direct-current stimulation), which applies weak electrical currents via scalp electrodes. These approaches can modulate neural excitability (e.g. for mood or pain treatment), but they don’t record signals.

- Invasiveness: BCIs range from completely non-invasive (no surgery) to invasive (surgically implanted in or on the brain). Invasive BCIs include intracortical electrodes (like what Neuralink does) that penetrate brain tissue, or subdural “ECoG” grids on the brain surface. Minimally invasive approaches sit in between – for example, Synchron’s Stentrode is an endovascular electrode implanted via the bloodstream into a brain vein, avoiding open-brain surgery. Invasiveness trades off signal quality against risk and ease of use.

Finally, BCI applications and maturity vary widely.

The most common applications:

- Many companies focus on monitoring (passive or consumer EEG headsets to track mood or attention).

- A few target modulation (e.g. neurofeedback or closed-loop stimulation therapies for depression, chronic pain, epilepsy).

- Others aim at direct control (restoring computer control or movement to paralyzed patients).

Depending on the applications, products span from research-only prototypes to beta-stage devices to FDA-cleared or commercial products. Emotiv and OpenBCI sell consumer EEG systems today, whereas Neuralink and Synchron are still in clinical trials of implantable devices.

Overall, non-invasive, safe, and easy-to-use BCIs are most mature, while high-bandwidth invasive systems (like Neuralink’s) are cutting-edge but still under development .

Meet the Makers

I have thrown around a lot of company names, so here is a rapid fire list of a few key players. It is a personal selection, trying to cover the range of what is being done in the space:

- Neuralink (founded 2016): Elon Musk’s high-profile neurotech venture that made BCIs cool. They raised over $1.2 billion so far and develop a robotically implanted intracortical chip. Neuralink performed its first human implant in January 2024. In February 2024, Elon Musk reported a patient could control a computer cursor by thought.

- Synchron (2016): A US/Australia startup spun out of research by Tom Oxley. It develops the Stentrode (endovascular BCI). Synchron has raised roughly $145M in venture funding. The first human implant was done in 2019, and the first U.S. human implant was performed in July 2022. Ongoing studies show paralyzed patients can use Stentrode to control digital devices (emails, shopping, etc.) in daily life.

- INBRAIN Neuroelectronics (2019): A Spanish firm pioneering graphene-based implants for both recording and stimulation. It has raised about $68M (including a $50M Series B in 2024). In October 2024 INBRAIN reported the first human use of its ultrathin graphene neural implant in a UK clinical trial. The trial implanted the device in brain cancer patients to test safety and compare graphene’s performance temporarily.

- CereGate (2019): A German startup turning already existing implanted stimulators (like spinal cord stimulators) into general-purpose BCIs. CereGate was founded in 2019 and has done feasibility trials using patients already implanted with neurostimulators. In a 2024 study, 18 of 20 patients (with existing spinal stimulators) successfully used their implant to control a computer, proving a “computer-brain interface” via a consumer SCS device.

- Neurode (2021): An Australian startup (founded by neuroscientist Nathalie Oliver) developing a wearable for ADHD management. Neurode’s device is a headband that both senses brain activity and delivers mild electrical stimulation to enhance attention. As of 2025 it is in clinical testing (no trials have been published yet).

Mental Health Promises

I. Reading the Mind's State

Non-invasive EEG-based systems have opened the door to passive BCIs that measure brain states like attention, stress, or cognitive load. Companies like Emotiv, Neurable, and Zander Labs use dry-electrode EEG headsets to detect patterns that correlate with anxiety, fatigue, or distraction. These readings are increasingly applied in neurofeedback, where users get real-time feedback on their mental state and can learn to regulate it. Common goals are to enhance focus, improve sleep, or reduce stress.

The data is imperfect and more on a mood/state level (these systems cannot decode exact thoughts or intentions). The tech is already being used by early adopters, biohackers, and researchers as a tool for emotional self-awareness and behavioral change.

II. Brain Modulation

A more active approach comes in the form of stimulation-based BCIs, often using transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). These methods apply low levels of electrical or magnetic energy to the scalp to change brain activity in targeted regions.

Samphire Neuroscience, for instance, develops a wearable tDCS device designed specifically for women experiencing PMDD, PMS, and similar conditions. Early trials suggest it may help reduce emotional distress and physical symptoms in ways that traditional pharmacology does not. Other companies are pursuing tDCS-based therapies for depression, anxiety, or PTSD.

(What is and what isn't a BCI is kinda unclear in this area. Those stimulation techniques are rather broad and little targeted. Without any sensing component, I personally find it questionable to be calling them BCIs, but their are usually included in that category. When they do target immediate relief or alteration of mental states, I see the argument. But long term tDCS therapy for depression I would not count into this class.)

III. Closed-Loop Solutions

The next step, and the real promise, is in closed-loop mental health BCIs: systems that can both read brain states and automatically respond in real time. Imagine a wearable that detects the early neural signs of a panic attack and counters it with tailored brain stimulation, calming audio, or guided breathing—without user input.

In more invasive contexts, responsive implants like NeuroPace’s RNS system, originally built for epilepsy, are now being investigated for treatment-resistant depression. These devices detect abnormal activity in deep brain structures and deliver corrective pulses within milliseconds. Though not marketed as mental health tools (yet), they hint at a future where emotional dysregulation could be treated with millisecond neural precision.

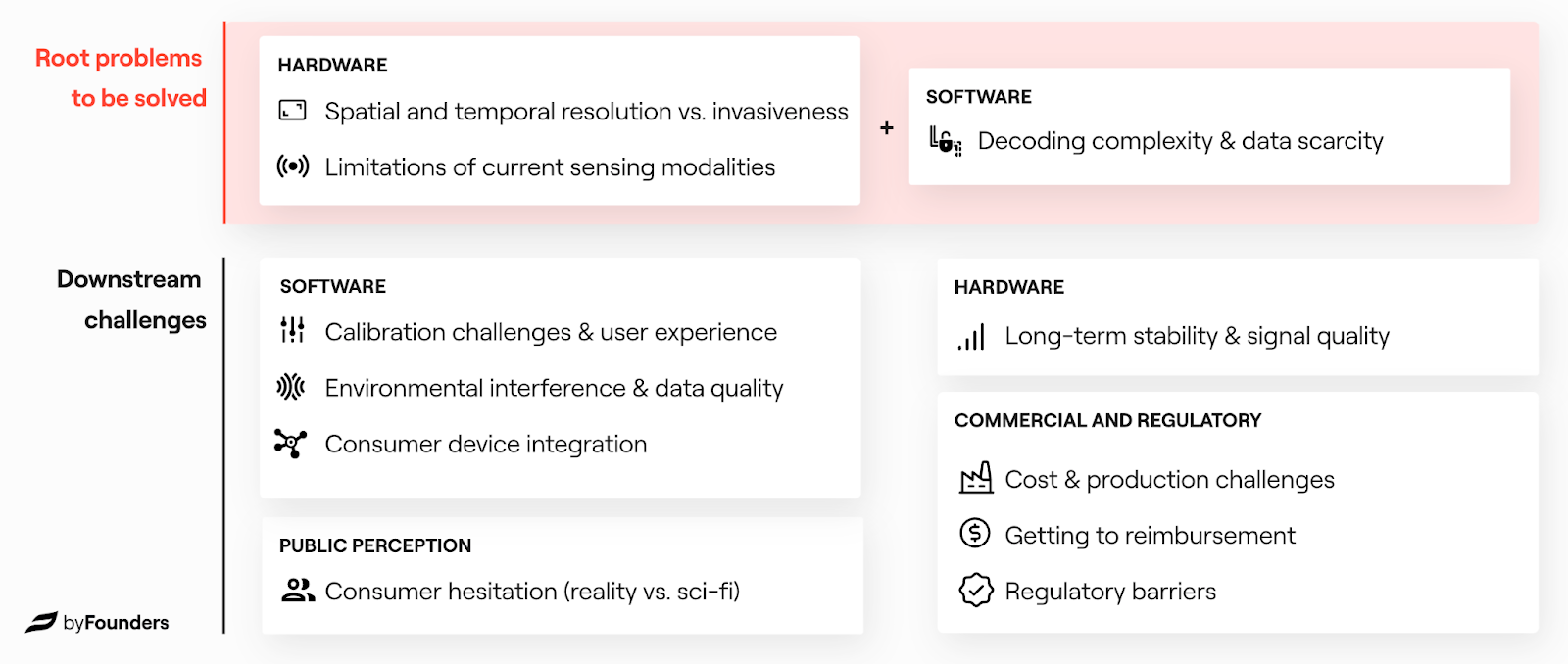

This graphic by byFounders does a great job at summarising what key challanges lay ahead in bringing the tech to market.

A Note of Caution.

Despite the enthusiasm, most mental health applications of BCI are still in early stages. EEG is noisy and spacially imprecise. Stimulation effects are hard to predict and can vary widely between users. Placebo effects are strong. Regulatory pathways are still being defined.

And then there’s the ethical question: Should we let software alter our emotions in real time? The more precise these tools become, the more this moves from treatment to augmentation. That line is already blurry.

Still, in a world where mental health demand far outstrips clinician supply, BCIs could offer new forms of scalable, personal support. Whether as a digital self-help coach, an emotional early warning system, or a neuromodulation headset, the brain is increasingly becoming both the source and the site of care.

Keep Reading

- byFounders: BCI investment thesis. A detailed look at the business case for the tech.

- Morgan Stanley: Primer on BCIs.

Company Showcase: Peers.

It is not always about the tech stack.

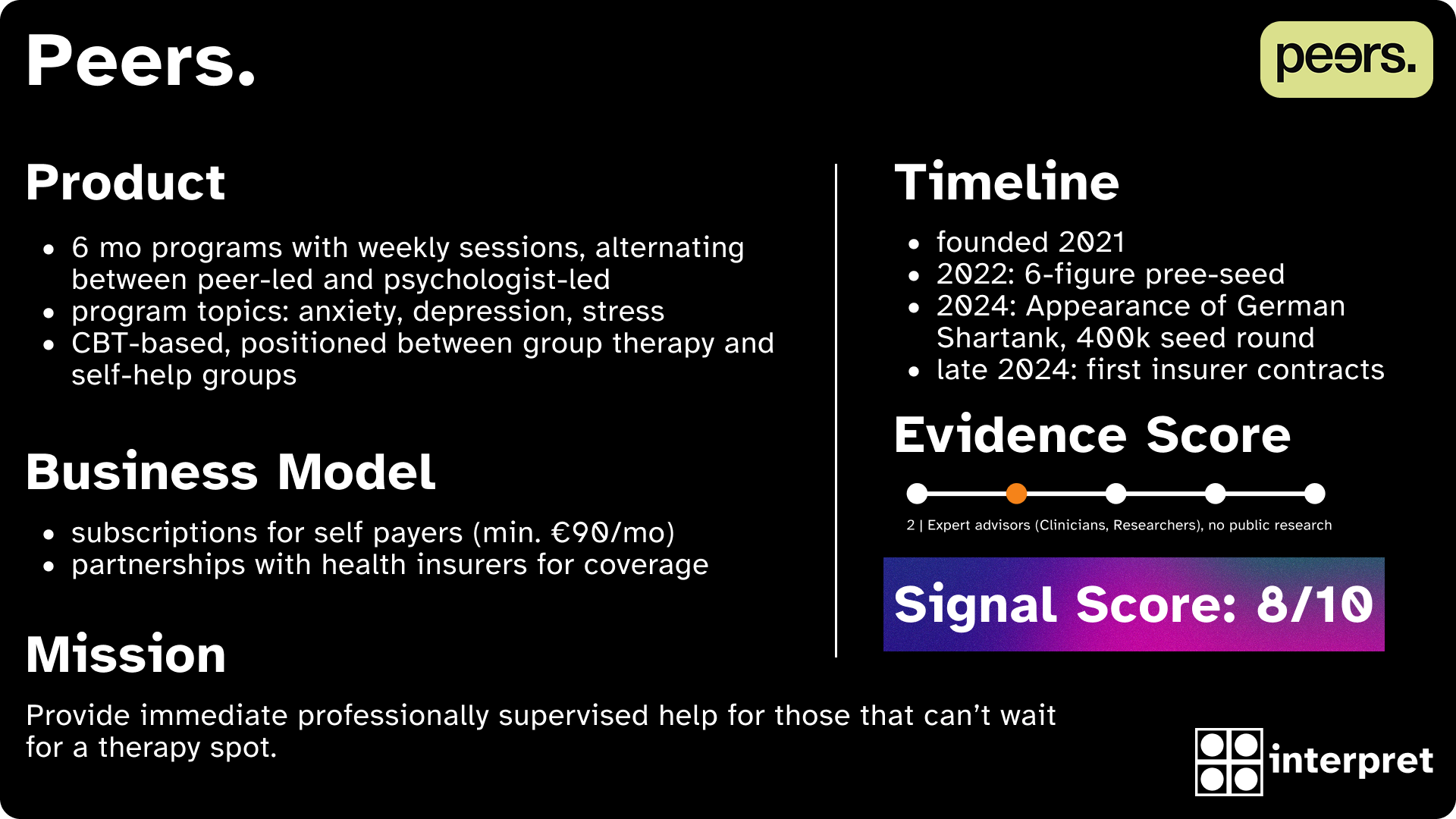

Mental health startups are often defined by their tech stack or AI promise. Peers takes a different route: it uses basic tech to improve mental healthcare. Instead of building another chatbot or mindfulness app, the Berlin-based startup delivers structured, psychologist-supervised group courses, which are positioned somewhere between self-help groups and formal therapy. This makes the company unique in a sea of online therapy providers like BetterHelp.

Programs & Peers.

Peers runs 6-month programs for people dealing with depression, anxiety, and stress. Participants are matched into small groups of 8 to 10 based on a proprietary algorithm fed by user-filled surveys. The program alternates between psychologist-led sessions and peer-only sessions, combining expert guidance with group accountability.

The sessions are held digitally, last 90 minutes, and are scheduled based on participant availability. Users can test the service for a month, with pricing starting at around €90 per month. The company also secured direct contracts with health insurers last year. Its model is based on the established effectiveness of cognitive behavioral group therapy, even though the product itself has not undergone clinical validation.

Founders and Vision

Peers was founded by Sophie Schürmann, Julia Maria Hautumm, and Max Kirschning. Krisching is leaving the team as CTO in the near future on good terms. The team brings together backgrounds in psychology, tech, and entrepreneurship. Their shared mission is to reduce chronic mental health deterioration by making professional support fast and accessible.

Traction & Funding

Peers reports user numbers in the four-digit range. In 2024, the team appeared on the German version of Shark Tank and secured €400,000 in funding from investors Carsten Maschmeyer and Dagmar Wöhrl, in exchange for 16% equity. Barmenia, one of Germany’s larger health insurers, is also backing the company as a strategic investor.

Ecosystem Relevance

Peers is something of an outlier in the current mental health tech wave, which is dominated by AI-driven diagnostics, digital assistants, and symptom trackers. From a user perspective it is rather undifferentiated though. The company is effectively competing with the likes of BetterHelp and MindDoc. To insurers the company might be an easier sell as the costs must be lower to comparing to those offerings with a focus on 1:1 therapy.

Rather than replace therapists, Peers builds a scalable system around them, aiming to preserve clinical quality while increasing reach. That positions it not as a tech product, but as a service model optimized for access and continuity. Effective execution, trust and marketing are the core success factors for the company.

Odd Lots – News & Research.

Keeping you up to date on psych tech.

I. Digital Prescription for DiGAs delayed to early 2026

Currently, if you get prescribed a digital therapeutic, you will receive said prescription on paper, with a code. Your health insurance then manually needs to process said prescription and approve it. This is why it usually takes 2+ weeks to get the DiGA. Due to technical difficulties, the Ministry of Health (BMG) moved the shift from paper to digital prescription to early 2026. Originally, the switch was planned for January of this year.

II. ARIA – the UK DARPA (Deep Dive Interview)

Government funded deep-tech research. That is what ARIA does. Their CEO explains the special structure and goals of the government owned entity in a long-form interview with an expert in RnD-Organisations. Why is this interesting in health tech?

A) They have multiple health tech related programmes (”Opportunity Spaces”)

B) Their idea of funding and research are quite unique in Europe.

ARIA is not about building new technology, but rather "shifting the conversation" about what is possible in said space. They want to start the “waves” that startups and VCs can then ride.

III. Always presume competence!

In this IEEE Spectrum article, Voikram K. Jasawal, Diwakar Krishnamurthy and Mea Wang outline their research into using AR headsets with specialized software as communication tools fpr people with Autism Spectrum Disorder. What is really impressive, is the fact that some users got used to the tool in a few minutes and could start typing quickly. They also descrive the co-development process of the solution with users in detail.

IV. Anne Wojcicki's nonprofit will acquire 23andMe

The former CEO of 23andMe will buy back her own company for over 300 Million through her own nonprofit. The company was initially set to sell to Regeneron which got outbid. Wojcicki was controversial as CEO and her decision-making might have contributed to the downfall of the company which ended in bankrupcy.

Alright, that's it for the week!

Best

Friederich

Get the weekly newsletter for professionals in mental health tech. Sign up for free 👇